Passenger Portraits

Passenger Portraits

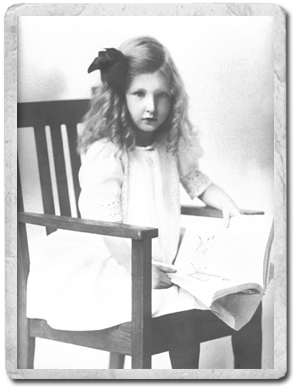

Dorothy (Dolly) Brooks

Nine-year-old Dorothy Brooks boarded the Empress of Ireland with her parents, Frank Percy Brooks and Henrietta (Hetty) Westwood, who immigrated to Canada in 1905, shortly after Dolly's birth. They lived in Toronto, where Frank worked as a joiner.

Mr. Brooks was a member of the Canadian Staff Band of the Salvation Army in Canada. The trip to England for the band's performances also provided Mr. and Mrs. Brooks with an opportunity to visit family members and introduce their daughter, Dolly.

Aboard the Empress of Ireland, band members travelled in second class, where Frank Brooks shared a cabin with his bandmate, George Felstead. Henrietta and Dolly were in third class along with Mr. Felstead's wife and two children.

Following the collision with the Storstad, Mr. Brooks did not know where his wife and daughter were. The rapidly listing boat made searching impossible, so Mr. Brooks had no choice but to leap overboard, unable to help his family. Henrietta managed to hold her daughter's hand until they both ended up in the water. A little while later, Mrs. Brooks was rescued and reunited with Frank in Rimouski, but Dolly was nowhere to be found.

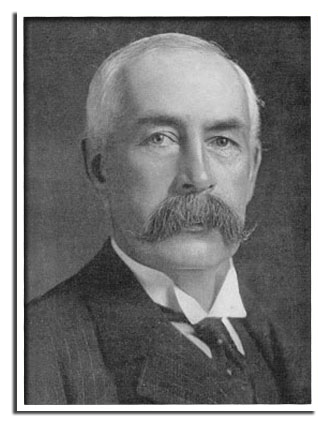

Born in Scotland, Sir Henry Seton-Karr trained as a lawyer and became a member of the British House of Commons. An avid outdoorsman, he enjoyed big game hunting, mountaineering, golfing and fishing for salmon. He also spent a great deal of time writing. In May 1914, Sir Henry was travelling in 1st class aboard the Empress of Ireland on his way back to Europe after a successful hunting trip in British Columbia during which he killed an average-sized moose. In Quebec City, the animal’s antlers were placed in the Empress of Ireland’s hold. Sixty-one-year-old Sir Henry Seton-Karr did not survive the shipwreck and was buried in the Mount Hermon cemetery in Sillery, Quebec City.

A section of an antler was recovered from the wreck in the late 1980s by Ontario diver John Reekie. It was likely Sir Henry’s hunting trophy, because in 1914, moose antlers were not typically displayed on walls.

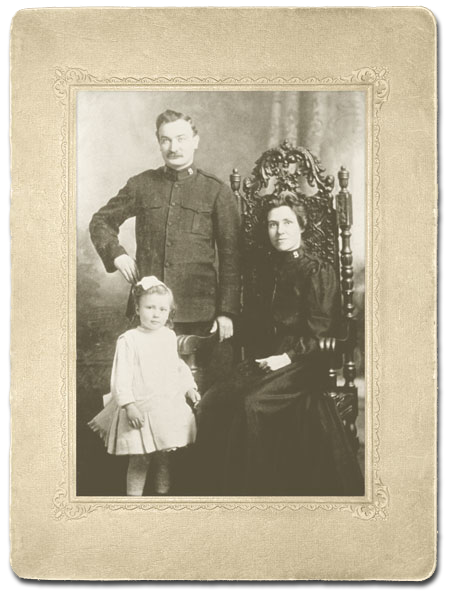

Grace Hanagan

Grace was 7 years old when the Empress of Ireland met its tragic end. She and her parents were on their way to London for the Salvation Army’s third International Congress. Grace’s father, Edward James Hanagan, was the Army’s Toronto staff bandmaster. Grace survived the sinking.

Grace was 7 years old when the Empress of Ireland met its tragic end. She and her parents were on their way to London for the Salvation Army’s third International Congress. Grace’s father, Edward James Hanagan, was the Army’s Toronto staff bandmaster. Grace survived the sinking.

On the train back to Quebec City on May 30, she told her story. “Father and I saw a flash of bright light through the porthole and felt the ship shake. Father said, “The boat is sinking,” and we ran with mother dressed just as we were. We climbed the stairs and went with father to the railing. Then we were thrown into the water. I lost mother and father and never saw them again. I sank deep into the water, and when I came back up, there was a piece of wood nearby. I hung on to it, then I saw a man in a lifeboat and called to him to take me aboard. He grabbed me and pulled me into the lifeboat. There was also a woman hanging on to the piece of wood, but I did not see her after that.”

Grace Hanagan was one of only four of the 138 children aboard to survive the disaster. She died in 1995, the last survivor of the Empress of Ireland.

Read Dennis Hanagan testimonies.

Major Henry Herbert Lyman

Montreal millionaire Henry Lyman and his father owned Canada’s largest pharmaceutical company. Lyman was involved in a number of organizations, including the Royal Geographical Society. He was governor of the Montreal General Hospital and director of the British and Colonial Press Service.

Montreal millionaire Henry Lyman and his father owned Canada’s largest pharmaceutical company. Lyman was involved in a number of organizations, including the Royal Geographical Society. He was governor of the Montreal General Hospital and director of the British and Colonial Press Service.

As a bachelor, he took care of his ailing mother for years. After her death, he married the daughter of Reverend Kirby of New York at age 57.

It was not until two years later that his schedule permitted him to leave America for Europe on May 28, 1914. Despite severe hearing loss, he rarely used his ear trumpet, and his young bride was constantly assisting him. The voyage was to be their honeymoon, but they both lost their lives when the Empress of Ireland sank.

Mabel Hackney et Laurence Irving

Mabel Hackney and Laurence Irving are, without a doubt, the best-known passengers aboard the Empress of Ireland. Irving was a well-known stage actor. Mabel Hackney was his partner on stage and in life. Laurence Irving’s production troupe was on a Canadian tour and gave its final performance at the Walker Theatre in Winnipeg on May 23. There was not enough time for the whole troupe to pack its bags in time for the Quebec City departure on May 28. Only Hackney and Irving, Harold Neville South and Elsie Roberts South, who were all in a hurry to return to England, managed to board the Empress of Ireland. The rest of the company boarded White Star’s Teutonic.

Mabel Hackney and Laurence Irving are, without a doubt, the best-known passengers aboard the Empress of Ireland. Irving was a well-known stage actor. Mabel Hackney was his partner on stage and in life. Laurence Irving’s production troupe was on a Canadian tour and gave its final performance at the Walker Theatre in Winnipeg on May 23. There was not enough time for the whole troupe to pack its bags in time for the Quebec City departure on May 28. Only Hackney and Irving, Harold Neville South and Elsie Roberts South, who were all in a hurry to return to England, managed to board the Empress of Ireland. The rest of the company boarded White Star’s Teutonic.

Neither Hackney nor Irving survived the sinking.

Ship’s Crew

Ship’s Crew

Captain Henry George Kendall

Henry George Kendall was born in England in 1874. At 15, he shipped as a sailor on a passenger liner. In the early 1900s, he was the Fourth Officer on a Beaver Line passenger ship. When Canadian Pacific bought it in 1903, the company retained Captain Kendall’s services. From 1908 to 1914, he captained various smaller passenger ships. On May 1, 1914, in Halifax, at the age of 40, Captain Kendall took command of the Empress of Ireland. On May 28, he left Quebec City as captain of the ship for the first time.

Henry George Kendall was born in England in 1874. At 15, he shipped as a sailor on a passenger liner. In the early 1900s, he was the Fourth Officer on a Beaver Line passenger ship. When Canadian Pacific bought it in 1903, the company retained Captain Kendall’s services. From 1908 to 1914, he captained various smaller passenger ships. On May 1, 1914, in Halifax, at the age of 40, Captain Kendall took command of the Empress of Ireland. On May 28, he left Quebec City as captain of the ship for the first time.

He survived the tragedy, but was deeply affected by it. After the inquiry in Quebec City, he returned to England and the Royal Navy as senior officer aboard the Calgarian. The Calgarian was torpedoed in 1918, but Kendall survived. After the First World War, he was Canadian Pacific’s Marine Superintendent in England until he retired in 1939. He died in London in 1965 at the age of 91.

________

The following is an unpublished interview

(in the early 1960's) with Captain Henry George Kendall,

about the arrest of Dr. Crippen.

![]()

James Frederick Grant

Twenty-six-year-old James F. Grant was making his second voyage aboard the Empress of Ireland as the new ship's surgeon. Born in Victoria, British Columbia, he graduated from McGill University in Montreal in 1913 and interned at the Montreal General Hospital.

James F. Grant was in cabin 300, which was set up as the dispensary for the ship's surgeon. More complex cases were handled in a small infirmary on the shelter deck at the liner's stern.

Dr. Grant barely survived the sinking. He was rescued by the Storstad after the collision and immediately set to work caring for the injured. He bandaged cuts, splinted fractures, treated burns and covered up the dead. He oversaw the transfer of the dead and wounded to the Lady Evelyn. Later, in Rimouski, Dr. Grant continued to provide bedside care to survivors in private homes. To many, he was the hero of the tragic event.

Roger Williams, Second Officer

Roger Williams was born on May 9, 1884, in Maryport, Cumberland, England. His father died at sea while captain of the S.S. Maling. Like many young men, he followed in his father’s footsteps: at 15, he was an apprentice navigator on a sailing vessel. After earning his Second Officer’s

Roger Williams was born on May 9, 1884, in Maryport, Cumberland, England. His father died at sea while captain of the S.S. Maling. Like many young men, he followed in his father’s footsteps: at 15, he was an apprentice navigator on a sailing vessel. After earning his Second Officer’s

Certificate, he looked for work aboard steamships and became an officer aboard an Anglo-American oil carrier. Roger Williams obtained his Captain’s Certificate and was hired by Canadian Pacific as Fifth Officer in 1912. He was promoted to Second Officer during the Empress of Ireland’s 191st voyage.

As the liner sank, he helped launch lifeboats until he himself was thrown into the water near the fore funnel and sucked in as water filled the structure. His body was recovered and is buried at the Canadian Pacific memorial on Rue du Fleuve in Pointe-au-Père.

William Clark

William Clark, from Liverpool, England, worked in the machine room as a stoker. He knew ships well, having done the same job two years earlier on the infamous Titanic. Mr. Clark survived the two shipwrecks. He described his experience: "I was fireman on both the ships. It was my luck to be on duty at the time of both accidents. The Titanic disaster was much the worst of the two. I mean it was much the most awfull. The waiting was the terrible thing. There was no waiting with the Empress of Ireland. You just saw what you had to do and did it. The Titanic went down straight like a baby goes to sleep. The Empress of Ireland rolled over like a hog in a ditch".

William Clark, from Liverpool, England, worked in the machine room as a stoker. He knew ships well, having done the same job two years earlier on the infamous Titanic. Mr. Clark survived the two shipwrecks. He described his experience: "I was fireman on both the ships. It was my luck to be on duty at the time of both accidents. The Titanic disaster was much the worst of the two. I mean it was much the most awfull. The waiting was the terrible thing. There was no waiting with the Empress of Ireland. You just saw what you had to do and did it. The Titanic went down straight like a baby goes to sleep. The Empress of Ireland rolled over like a hog in a ditch".